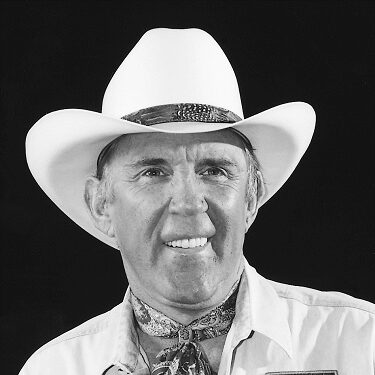

Ray W. Scott, Jr.*

Class of 2003

- President Ray Scott Outdoors, Inc.

I have a graveyard of unsuccessful ideas, but you must never be afraid to try or to fail.

Ray Scott Jr., the oldest of three children, was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression. Originally, Scott's father was a cattle farmer in Kentucky, but in 1923 the Scotts went broke after the government destroyed their cows during an outbreak of hoof-and-mouth disease. The couple moved to Alabama, where they found work on a dairy farm. When Scott was a year old, he and his parents moved out of his grandmother's home into a rented duplex.

Scott's father had an entrepreneurial spirit and a motto: "Nobody has any money, but everybody has a nickel." With that in mind, and thanks to his connections at the dairy farm, he started his own pushcart ice cream business in 1933. He sold ice cream for a nickel, making a two-cent profit off each sale. Eventually, he supervised 10 carts. Several years later, he tried his hand in the restaurant business. Finally, at the end of World War II, he went to work for the post office as a railway clerk.

When Scott was five, his grandfather died, leaving Scott's father as the family patriarch. Three of Scott's uncles, who were in their teens, came to live in the small duplex. "There were seven of us in that one-bedroom apartment," said Scott, "but we were happy. We lived a good, wholesome life. There wasn't much money, and we all had to work, but we did it together with a lot of laughter." In 1940, Scott's mother, a hairdresser who worked from home, saved enough money to buy a lot in town. With the help of a federal loan, the family built a small house in a working-class neighborhood.

At the age of eight, Scott got his first paying job, earning $1 a day delivering groceries on his bicycle. In the summer, he cut grass and helped his father and uncles sell concessions at the Montgomery baseball stadium. When he was not selling peanuts at the games, he sold parking spaces on his grandmother's 100-foot driveway. "On busy game days, I could earn $15," he recalled.

Scott's father taught him to fish when he was six. He took to the sport right away, and it became a constant in his life. When he was 16, he formed the Bluegill Fishing Society. He and his friends, who each paid 25 cents to join, went on short fishing trips in his father's 1939 Chevy. Scott loved fishing and often wished he could find a way to make a living at it.

In school, Scott struggled with dyslexia. His parents were concerned, and when he was in the seventh grade, they sent him to a local military school. His grades improved, and he returned to public school the following year. But he was soon distracted by sports and socializing, and he failed the eighth grade. The next year he passed, but he returned to the military school in the ninth grade on a football scholarship. The team was successful and became all-state champions.

After high school graduation, Scott said he was "a lost ball in high weeds." He failed to earn a football scholarship to what later became Auburn University, which was his first choice. Then he began to wonder if he had a calling to be a preacher. His pastor recommended Birmingham's Howard College, a small Southern Baptist school later called Samford University. He earned a football scholarship to that school and joined its track team. To supplement his scholarship, he worked for Vulcan Insurance while collecting premiums for funeral insurance. This job took him into Birmingham's worst neighborhoods, but Scott soon became the company's top salesman.

In 1954, seven months after joining Vulcan, Scott was drafted into the U.S. Army. He was shipped off to Germany, where he played for his Army company's football team. Upon his discharge, he used the GI bill to pay for his education in business administration at Auburn University. After graduating, he joined Mutual of New York Insurance Company (MONY), which sent him to a one-week sales course. But after using its methods for a month, Scott had not sold one policy. He took MONY's sales brochures to the backyard and burned them. He returned to work using his own sales and referral system, and soon he had sold more than $100,000 worth of insurance.

For the next 10 years Scott stayed in the insurance business and at one time had his own agency. Yet he always found time to indulge in his favorite pastime, fishing for bass. In 1967, an idea suddenly came to him as he waited out a storm to go fishing. He would sponsor a national bass fishing tournament trail where anglers would compete not only for a large cash prize, but also for national recognition. Using the same format as a golf tournament, he would have entrants for the bass tournament pay substantial fees to compete. Scott wanted to make bass fishing more than weekend recreation. He hoped to unite bass anglers not only to compete but also to further the sport through shared knowledge.

Convinced his tournament concept would work, he resigned from his insurance agency to devote his full-time attention to the new idea. Despite a lack of funds, he was determined. "You can afford to be daring when you're convinced your philosophy and system can successfully take you into any market place, even if the market is brand new, untried, and untested," he said. "Frankly, poverty was my greatest asset. It is very motivating."

Scott had 106 participants in his first tournament. His idea for a national bass fishing tournament trail turned into an organization called the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society. He applied to his new venture the same sales and referral techniques that had proved so successful in his insurance business. Finally, he had found a way to earn a living fishing.

Looking back over his career in insurance and with the fishing society, Scott said he never feared pursuing a new idea. "Taking the first step can be the hardest, but it is the most important step of all," he said. "Success goes hand in hand with imagination, tempered by hard work and dedication." And although he had much success in life, Scott had his fair share of slumps too. "I have a graveyard of unsuccessful ideas," he said. "But you must never be afraid to try or to fail."

Scott said he was deeply honored by his Horatio Alger Award and was awed by the work of the Association with America's deserving youth. "The Horatio Alger Association sees that spark in the darkness," he said. "They take these young people and give them the fuel and encouragement needed to be a success. That really touches me, and I am so pleased to be even a small part of their personal journey."