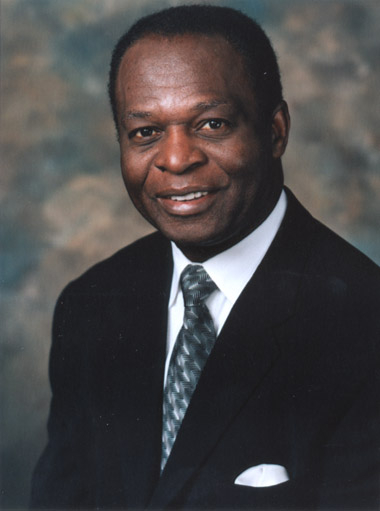

Louis C. Brock*

Class of 2002

- President Brockworld Products, Inc.

Most people have an inner person that holds the keys to their social, leadership, and relationship performances.

Lou Brock, the seventh of nine children, was born in 1939 in El Dorado, Arkansas, to sharecropper parents. When he was two, his parents separated, and his mother moved with the children to Collinston, Louisiana, where the family continued to live as sharecroppers. Their home had no running water and no electricity.

Everyone in the Brock family had to work in the cotton fields, even five-year-old Lou. When Brock was still a youngster, his mother remarried, and the family moved to a house that traditionally boarded the local schoolteacher. For several years, Brock's teacher lived in his home and made sure he kept up with his schoolwork. "She was my first positive role model," he said. "She introduced me to a world that was far away from what I knew. I had never been exposed to someone who had gone to college. Just listening to her gave me the idea that maybe I could go to college."

That same teacher opened another important door for Brock. One day in class, he shot a spitball with a rubber band, and, rather than hitting the girl he intended, it hit his teacher. Brock's punishment was to stand in front of the classroom and read out loud from a magazine. The article he was assigned to read was about baseball. Brock became enthralled with the feats of players like Jackie Robinson, Joe DiMaggio, Stan Musial, and Roy Campanella. But what really caught his attention was the fact that those players were making $9 a day for meal money. To young Brock, that seemed a fortune. Later that day, when Brock's class went out to play baseball, he was assigned to play first base. He challenged himself to catch all the balls thrown to him. He did his best and in the process fell in love with the game. From then on, he tried to learn all he could about baseball.

The radio became one of Brock's major forms of entertainment. He was a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, and he admired Robinson's ability to break down racial barriers. "Listening to the radio gave me a chance to dream," said Brock.

In high school, he played baseball and excelled in science and math. He was on the math and chemistry teams, representing his high school at the state finals. After graduation, Brock knew he wasn't going to be invited to play baseball for any colleges. He went to work baling hay, a job that paid only $3 a day, but he knew manual labor was not going to be his future. The next day, Brock took a bus to Baton Rouge and told the registrar at Southern University that he wanted to work his way through school. He eventually earned a baseball scholarship and led his team to the World Series Championship of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics.

During his senior year, Brock signed a contract with the Chicago Cubs. He went into the minor leagues that year but didn't stay long. Within three months, he was playing in the major leagues. Three years later, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he played for 17 years. Brock's career in Major League Baseball (MLB) was phenomenal. In 1977, he broke Ty Cobb's all-time record of 892 stolen bases, one of the most durable records in MLB history. In 1985, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Looking back, Brock said his only goal as a youth was to get a college degree and become a teacher so that he could improve his lifestyle. "I didn't have any grand dreams," he said. "I was just responding to the challenge in front of me. As a child, I was challenged to do well in school because I had a teacher living with me. When I went to college, I was challenged to prove to my fellow athletes that I was worthy of a scholarship. I have always responded to the challenges presented to me by the circumstances I was in at the time. If you're successful in what you do over a period of time, you'll start approaching records, but that's not what you're playing for. You're playing to challenge and be challenged."

Of course, Brock was quick to say he had a lot of help along the way. The teacher who lived with his family was one of his first mentors, but later he responded to his high school baseball coach. After that, there was Buck O'Neal, MLB's first black coach. "Buck never met a person he didn't like," said Brock. "He was excited about life, and he instilled that in me."

Asked for his impressions about the Horatio Alger Award, Brock said, "I am honored to receive the Horatio Alger Award, to know that those I have admired for many years have found me worthy to join them. But I am especially excited to be part of an organization that does so much to help at-risk youth."

Brock said that when he was young, he didn't know what his purpose was in life. "I think I was destined to play pro ball, but the way to get there was not clearly defined," he said. "No scouts were interested in me when I was in high school. Going out for baseball was my second chance at staying in college. Since then, I have always believed in second chances."