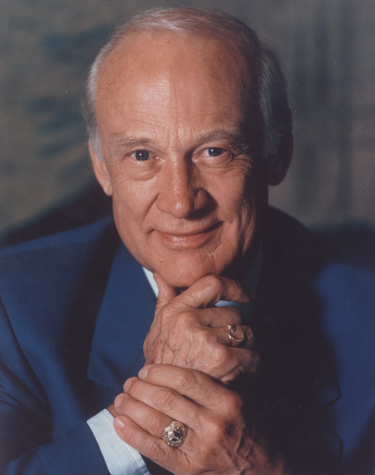

Buzz Aldrin

Class of 2005

- Board Member Buzz Aldrin Ventures, LLC

- Astronaut, Apollo XI Buzz Aldrin Space Institute

Shoot for the moon'you might get there!

Edwin Eugene "Buzz" Aldrin Jr. was born in 1930 in Montclair, New Jersey, the youngest of three children and the only boy. His father, an aviation pioneer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, entered the reserves in the late 1920s and became an aviation fuel expert for Standard Oil Company. His father's skills as a World War II pilot led young Aldrin to dream of becoming a pilot.

During Aldrin's childhood, his father was called back into wartime service. His father's visits home were always short, and Aldrin felt that although his father was interested in him, his father was often emotionally remote. Aldrin's mother suffered from periodic depression and a dependency on alcohol. In the often-closed society that was suburban postwar America, people rarely discussed such afflictions openly. Aldrin's early adulthood became marked and scarred by his mother's withdrawal and her inability to provide emotional support. Aldrin inherited his mother's shyness, but he had an inquisitive nature. His ability to focus his attention on a problem until he found a solution developed his creativity and inventiveness.

Between the ages of 9 and 15, Aldrin spent his summers at a camp in Maine. He enjoyed the camaraderie and free adventure of those days. A natural athlete, he joyfully participated in sports and developed a competitive spirit that characterized much of his later life. Aldrin was the quarterback of his sophomore football team, but he gave up football in his junior year to concentrate on academics.

He had set his sights on the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. To prepare himself, Aldrin spent his last summer vacation in a prep school to study math, physics, vocabulary, and English. He did well at West Point and graduated with honors in 1951 and third in his class. He applied for and was accepted into the U.S. Air Force as a fighter pilot, finishing his training in time to take part in the Korean War. He flew in 66 combat missions and shot down two MIG-15s. He went on to serve as a flight commander in West Germany, and returned to the United States in 1959.

Aldrin's inquisitive nature led to an interest in pursuing the new science of astronautics, and he entered the PhD program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His graduate thesis was titled "Line of Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous," which developed and described the techniques for orbital intercepts. Aldrin had found his calling. His work was pertinent, practical, and innovative enough for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to take notice and to use his theory throughout the space program, from the Gemini missions through the International Space Station.

Aldrin joined NASA in 1963 as a member of the Gemini program. His first space flight took place in November 1966 on the Gemini XII mission. On that flight, he established a new record for space walking. Apollo VIII was man's first flight around the moon, and Aldrin served as backup command module pilot. On July 20, 1969, Aldrin and Neil Armstrong made their historic Apollo XI moon walk, becoming the first two humans to set foot on another world. This unprecedented heroic endeavor was witnessed by the largest worldwide television audience in history.

Upon returning from the moon, Aldrin embarked on an international goodwill tour. He was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, one of this nation's highest honors. This unprecedented celebrity and scrutiny, however, began to make Aldrin feel isolated and vulnerable. Never an extrovert, he experienced considerable anxiety speaking in public.

In 1971, Aldrin left NASA and returned to the Air Force. He took command of the Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California, but it was a difficult transition. He had been at MIT and NASA for 11 years and found his return to be unsatisfying. What he didn't fully comprehend at the time was that he had been slowly falling into depression since the Apollo XI mission. Aldrin was predisposed to the condition, but unprepared for it. His maternal grandfather had committed suicide years before as a result of depression. In 1968, shortly before his moon walk, Aldrin's mother also ended her own life.

Aldrin began taking antidepressants and thought he had his problem under control, but soon his depression deepened and was complicated by alcoholism. In 1972, he retired from the Air Force. For the first time since his days at West Point, he began leading an unstructured life. At the age of 41, he stopped and examined his life. When he was young, his father expected him to set goals. After he accomplished one, he was encouraged to set another, even bigger one. Now, he was forced to decide what he wanted out of life.

Aldrin underwent psychotherapy, began to exercise regularly, and took medication for depression. He learned to have patience, perseverance, and an evolving faith that helping others is a means to helping oneself. One of his new goals was to bring depression into the open, thereby encouraging the public to treat it as one does a physical infirmity. Aldrin's dependency on alcohol took longer to conquer, but in 1978 he finally achieved sobriety.

Since those dark days, Aldrin has written four books, including his early autobiography, Return to Earth. "The title of that book is significant. The difficult part of my life was not going to the moon; it was what I had to face when I returned," says Aldrin, who remains at the forefront of efforts to ensure continued U.S. leadership in manned space exploration. He lectures and travels worldwide, discussing his ideas for exploring the universe.

Aldrin's advice to young people is to "move through life with arms stretched out as far as possible to find and pursue opportunities. You will discover they abound. When things you want don't work out, remember that something else is sure to come along. I applied twice for a Rhodes scholarship but never got it. If I had, I'm sure my career would have taken me in a different direction. It's important not to give up. Persevere to achieve the most difficult goals. I was turned down the first time I applied to NASA, and I did not achieve sobriety the first time I attempted it. Perseverance through difficult times is the key to success. I participated in what will probably be remembered as the greatest technological achievement in the history of the world. I traveled to the moon, but the most significant voyage of my life began when I returned from where no man had been before."